Years ago, I made a house call to visit a grizzled retired police detective. I was prattling on about progress at the University of Portland when he interrupted, pointed a finger at me, and growled, “In thirty-five years on the force, I learned one thing, only one thing. Do you know what it is?”

“No.” I hadn’t a clue.

He squinted his eyes and harrumphed louder, “Assume nothing”. He repeated, jabbing his finger, “Assume nothing”.

How timely his wisdom seems now.

More data comes in daily about Covid-19, but we know little of what life will look like a week, month, or year from now. How long will the elderly and sick be vulnerable? When will I be able to hug my mother again without putting her at risk? In a month will I have a job? If I do return to work will I get sick? How long can I pay the bills and feed my family? When will I be able to go to Church and receive the sacraments? Can we assume anything?

In the midst of the Great Depression, President Franklin Roosevelt said, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” It boosted people’s spirits enormously even though it was mostly illogical. We fear many tangible realities now as people clearly did then; some fears have names, but Christians can lump them all under one label. They are our Lenten crosses.

We may have planned to fast from desserts or alcohol or to give alms in donations or through service, but now we are being asked to fast from one another’s company, from receiving Jesus in the Eucharist, from the ordinary activities and kindnesses through which we are accustomed to feeding one another.

How difficult it is to be told the most pastoral thing most of us can do, clergy, religious and laity alike, is to stay away from other human souls. How hard to accept that cross. How ironic and profound for believers to be challenged to do precisely this as our Lenten journey progresses toward the Cross of Christ and beyond to his resurrection.

It is a wholly unanticipated pilgrimage of faith that we are all on together. Covid-19 is the social equalizer we never saw coming. It sounds more like a brand name for acne lotion, inane yet insidious like the serpent invading the Garden. If it was ever a challenge to preach on a gospel featuring lepers previously, no longer. We are all lepers now.

It is an odd way to discover our oneness with the rest of humanity, rich or poor, of any color or faith, from Pole to Pole, to be unclean. How quickly we have conditioned ourselves to people stepping into the street as we approach on the sidewalk. To St. Paul’s litany in The Letter to the Galatians, “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free person, there is not male and female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus,” [3:28], we can add “there is neither clean nor unclean.”

It is an odd way to discover our oneness with the rest of humanity, rich or poor, of any color or faith, from Pole to Pole, to be unclean. How quickly we have conditioned ourselves to people stepping into the street as we approach on the sidewalk. To St. Paul’s litany in The Letter to the Galatians, “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free person, there is not male and female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus,” [3:28], we can add “there is neither clean nor unclean.”

And how remarkable that this call to oneness as the necessary price for defeating an invisible foe requires an implicit embrace of our community’s spirituality, “The Cross, Our Only Hope.” We are being asked to accept the pain of social isolation by remaining tethered in place in vicarious imitation of the crucified One.

We are all are familiar with the value of sacrifice, and hope in the cross isn’t really news. St. Paul wrote nearly 2000 years ago, in his letter to Christians in Rome, that we are buried with Christ through baptism. Faithful people know today, as did those early Christians, that our commitment to Christ pledges us to die along with him. It is the necessary pathway to life. Our spirituality is not so original as it is necessary.

One doesn’t even need to be a churchgoer to realize that a little pain brings gain in the gym. We acknowledge the benefits of giving up junk food and cutting carbs to lose weight. High schoolers can enhance their odds of getting a college scholarship by spending more time reading books than playing Grand Theft Auto. Cultivating self-discipline allows us to develop good habits that shift perceived needs into the column of mere wants. The idea of sacrifice has universal appeal. The difficulty lies in stepping up to it.

But the crosses stemming from the virus require us now to sacrifice needs for needs, to eliminate daily human contact deemed essential by most of us to benefit the common good. It makes sense; it’s just hard. Neither is Jesus’ Cross the paradox it seems. It has an elegant logic: if we want to live we must die someday. But what is ever so maddening about the crosses of this Lent is that we are dying to what we need in order to keep on living now.

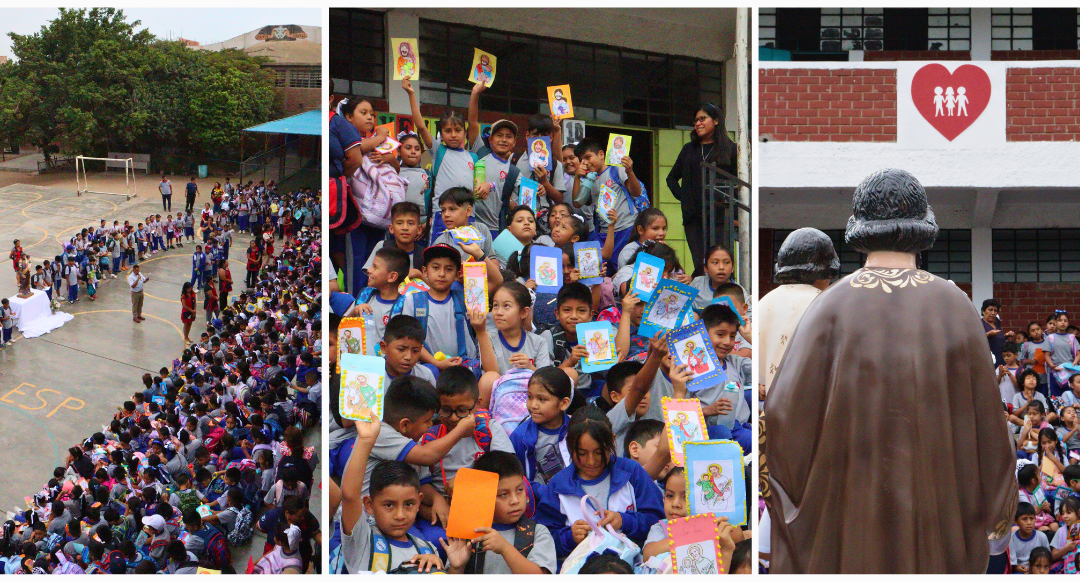

I would qualify my old detective friend’s advice about assuming nothing a bit. We can assume that we are not really alone, that grace envelops us in many ways: the generosity of volunteers delivering food to seniors; the heroism of health care personnel operating with jerry-rigged safety equipment; the constant restocking being done by supermarket employees with aching feet and sore backs after double shifts – all wondering whether their dedication will result in them communicating the virus to their families. We are surrounded by unknown heroes emulating in ways great and small the sacrifice of Jesus.

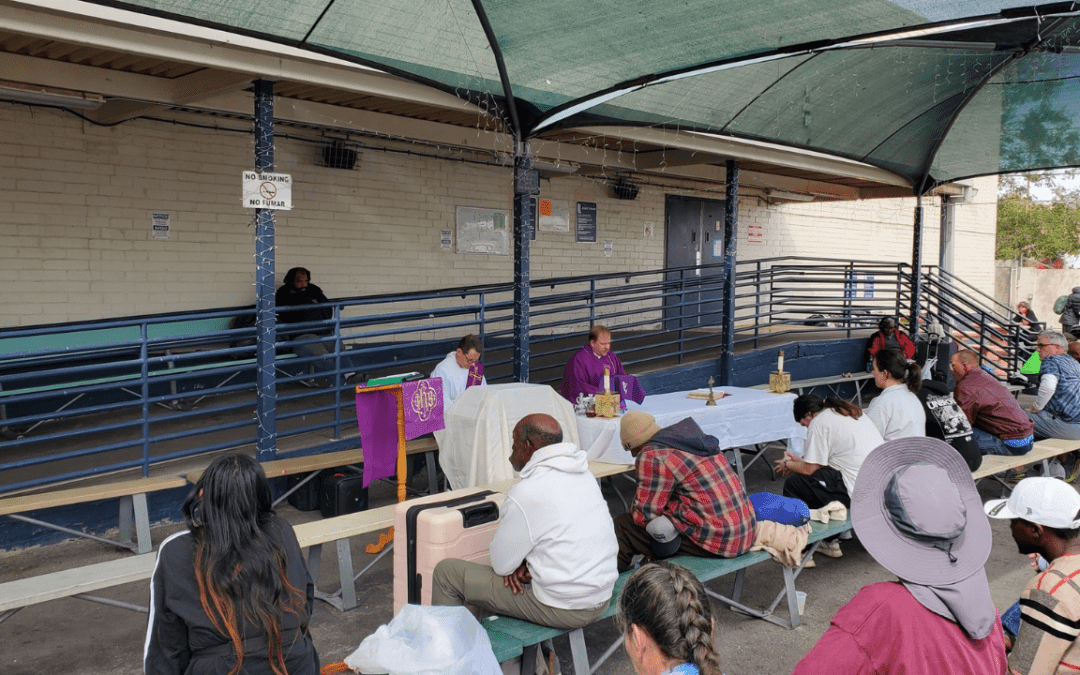

We are believers whose faith is embodied by the Sacraments, but the Church itself and the people of God who comprise it are sacraments too. If we cannot receive the Sacraments we crave right now, we can appreciate that the concrete mercies emanating from all those bringing Christ to others are helping to sustain us in body and soul.

Rarely has an entire society and never has the whole world been asked to express its unity by shouldering the same cross of social isolation while continuing to care for the sick, the poor, the helpless, and the grieving as now. So often we have pondered another paradox, the apparent contradictions of the Beatitudes. How can those who suffer be blessed? But we are living them now and being abundantly blessed by those sacramental people. It is not Holy Communion but a very real form of communion, the Body of Christ enfleshed, and it is a more potent, enduring reality than any virus.

Its many manifestations reflect the love of God that penetrates every speck of creation even smaller and more powerful than Covid-19. That grace at work is the one thing we can assume and in which we place our hope this most strange, fearful, and paradoxically hope-filled Lenten Season.