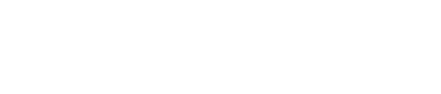

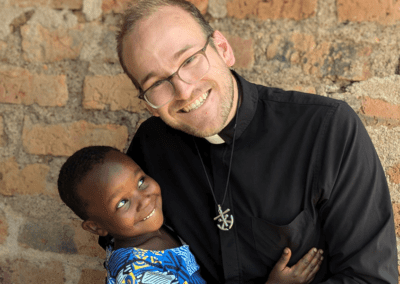

In the “Letters from Nyumbani” series of reflections, Moreau seminarian Keenan Bross, C.S.C., will share his experiences during his pastoral year at St. Felista Catholic Church, a Holy Cross parish in Utegi, Tanzania. The series title includes the Swahili word “Nyumbani,” meaning “home,” a reminder that for Holy Cross religious, “Often we must make ourselves at home among more than one people or culture” (Constitution 2 of the Congregation of Holy Cross).

———

“Sherehe – The Feast of the Poor”

“I normally don’t allow our outstations to have sherehes, they are too much work and cost too much money,” our Pastor Fr. Innocent, C.S.C., explained to me on our drive to Mang’ore outstation (one of St. Felista’s seven chapels, along with themain church, that comprises our Parish). “At most once per year, I’ll let them have them.”

Sherehe, pronounced “shey-rey-hey,” is the ubiquitous Swahili term that gets clumsily translated to English as “party.” It might also be festival, celebration, or thanksgiving. You can’t go very long in this part of the world without running into one. In fact, my very first evening on this continent, I made my way with some fellow seminarians and priests to our neighboring convent, sat in a big circle, and had my first sherehe. The event was a combination of birthdays and graduations that my jet-lagged self partially understood.

The first thing you notice about a sherehe as a US Americanis that they are highly structured events. Forget about walking around, picking your chips and dip, your drink of choice, and mingling with new friends. In East Africa you take your seat, buckle up, and enjoy the show.

There are a few essential elements. In a Catholic setting, we most often begin with Mass, sometimes evening prayer or the rosary. After this, an emcee or two are designated to manage the rest of the event, often with a numbered list of activities to attend to. These can include dances from liturgical dancers, performances from choirs, custom-made poems for the occasions, or thanksgiving speeches from dear friends. There is always a hierarchical crescendo with the most important guests having the last (and often longest) word. And then finally, a blessing over food pronounced by Father or Seminarian or whoever is most fitting.

A basically universal component of the sherehe, lodged between blessing and eating, is the cutting of the cake. Yes, cake. Somehow a rather dry, light, frosted version of the Western birthday or wedding cake is nearly universal in these celebrations, though with its own customs. Those most important guests who spoke at the end each put a hand on a massive knife together and, at the countdown of the emcee, gently together slice into the cake — ceremonially commencing the celebration. Then, servers descend upon the scene to actually cut the cake into small bite-size pieces, stick toothpicks in them, place them on trays, and deliver them back to the most important guests. Then, in descending order, the guests actually feed one another — hand to mouth — pieces of cake as a sign of respect and communion. Only then does the meal, waiting somewhere off to the side in hot-trays, begin to be served.

In only three months here, I have already attended countless of these sherehe’s. Some are for major events like First Masses, Priestly and Diaconate Ordinations and Final Vows. Some are for very small ones, like at the convent my first evening, or in our own rectory on the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows. And many yet to come, like that of Mang’ore in one of our seven outstations. But the amazing thing is this: whether 15 or 1,500 people are in attendance, you can expect the same basic rubric. Prayer → entertainment → speeches → blessing → cake → feast.

Moreover, you can expect the same basic challenges. To be plainly honest, at first, I found the events exhausting. For one, depending on what language is being spoken, I might be completely lost the whole time. Then I am really not sure how to be composed as the only white man present, normally at the “high table” — can I take out my phone to try to translate what’s going on? Can I step away to use the restroom? Might I be called upon unexpectedly to give a speech? (which has happened). And after all is said and done, I’m always a bit afraid of what the food cooked in enormous pots for hundreds of locals might do to my stomach (though I’ve yet to have any issues). Truly, I have to admit, I have more than once longed for the Buffalo Chicken Dip and mingling of a Superbowl watch party.

But as tiresome as these celebrations can be, they are also effective. When the goal is to celebrate with as much vigor and as many people as possible, they do the trick. People really come out of the woodwork. Churches that are never quite full end up seating-room-only, entire football fields can be covered in tents, and even minor groups can feel the full force of the parish’s support. The key component (with sherehe’s the same as with poor graduate students in the United States) is food. So long as there is food, they will come. In fact, food is almost used to hold people hostage — rice, meats, ugali, all kept warm in massive pots — until all of the speaking is done. Then, people eat. Really, they eat. Unlike home where we eat and chat and linger, eating is the final act, done alone in your chair where you persisted for most of the gathering. It’s done swiftly and silently — people even look at me funny when I try to strike up too much conversation. When it comes to eating, people mean business.

Sherehes, in part, are so popular because they’re an effective form of “business.” They often serve the dual-function of celebration and fundraiser. It’s a bit of an investment — first, the group works to put together enough food and animals to host the sherehe. Sometimes, they request a mchango (a small donation), normally less than $1, of invitees to help cover the cost and go towards the cause. Then, during the long section between prayer & eating, folks from every corner of the community come forward to offer $3 here, $5 there. Some of the wealthier members of the community might be called by name, even given a chance to speak, and donate a larger amount equivalent to $10 or $15. Then comes the “guest of honor,” someone who’s been specifically invited to give the main speech and offer the main mchango, gets the last word. He might talk for fifteen or twenty or even thirty minutes, be it about politics or religion or community affairs, before making his contribution — often as much as a few hundred thousand shillings, over $100. The group can use these funds to buy new speakers or choir uniforms, install a floor or windows in their church, or really just about anything. I’ve been told you can expect to raise one or two million shillings, $300 – $700, with such sherehes. As much as Fr. Innocent is hesitant, because of the work involved, and because of what those mchango demand of our poor parishioners, he knows they are an instrumental part of the workings of our parish.

As for myself, I’ve grown comfortable at the sherehes. For one, I know what I’m getting into, and just set my mind to enjoy it. And when I can, I find a way to sneak off and meet people, trying to use them as opportunities to build relationships and invite people to become leaders in their local churches. For the most part, I’ve withheld any kind of major judgments about this way of gathering. Sure, it’s much more formal than my own culture, with structured program after structured program. And it’s so plainly hierarchical from top to bottom, start to finish. But it’s also wildly inclusive – basically anyone, any neighbor, any parishioner, can come and participate. More, it’s constitutive of community life. All the speeches and dances and songs function as a statement: this is who we are, this is what we value, and this is where we’re going — even if that vision is being directed by just a few. And even though it takes a darn long time, often many hours, to put rice on your plate, Isaiah’s prophecy is fulfilled: You who have no money, come, buy grain and eat; come, buy grain without money, wine and milk without cost! (Isaiah 55:1).

Because at the end of the day, what is a sherehe? It is when the poor gather, and, out of their lack and their need, they celebrate a day of great abundance, of wine and milk, goat and beef, chicken and lamb. And even these poor farmers of Utegi are filled with the riches of their faith, their community, and a foretaste of that sherehe which will have no end.

———

“Seminars, Young Adults, and the Kingdom of God”

“Frateri Keenan, we are having a semina tomorrow in Kotwo, will you be there?”

Just after receiving the oversight of our Young Adult Ministry here at the parish, I received my first duty — a phone call simply informing me that the youth of one of our churches in Kotwo had organized a semina the following day, and my presence would be appreciated. I agreed, not yet sure what a semina is, and the following morning my fellow seminarian Katongole dropped me five miles away in Kotwo with a small talk prepared on my phone, everything needed for a communion service in my bag, and my bicycle to ride home at the end of the semina, whenever that might be.

When I arrived there were 10 or so young adults, or vijana in Swahili, ranging from 20 to 30 years old, eager to begin. It was clear that I was the de-facto leader, but I of course didn’t actually understand what was even planned for the day, and what I was supposed to be leading. So I asked a few questions about what we had planned, opened us with prayer, and invited everyone to make introductions. Turns out, we had young adults present not only from Kotwo but others who had walked from the surrounding villages.

Over the course of that day, I got a basic picture about what a semina is. The young adult leader explained that we would be having three mada, three topics, one on spirituality, another on health and culture, and the last on entrepreneurship for young adults. We had one young leader who was a nurse prepared to speak on health and culture, another with a business degree for entrepreneurship, and I myself was tasked with spirituality. Over the course of the day, I was impressed by how interested these young people were in hearing one another’s expertise. Everyone had notebooks out and were attentive to hour-long presentations that meandered, for example, from nutrition to modest clothing to the dangers of female genital mutilation. I got the sense that these young adults really appreciated the chance to speak openly and honestly among themselves about the challenges they face, somewhat often, on their own. They were genuinely hopeful that they might learn something, for instance in the business realm, that could help them get their feet on solid economic ground as they try to build their lives as rural farmers. We wrapped up five hours later with Holy Communion and the communion of some rice and beef as the rain clouds began to roll in. There was a sense of excitement about our future together as the young adults of the parish as I got a couple of phone numbers and mounted my bike to race back before the rain.

Little did I know that my first semina that day would be far from my last. “We’ve got a big seminar for all the young adults at the end of October,” Fr. Innocent explained to me, “and in order to prepare, you’ll organize smaller seminars in the rest of the outstations to prepare them for October.” Quickly enough, then, this month became the month of the semina. We set a couple of Saturdays, and I got to work sorting out how to actually prepare for one of these things.

In my more American leadership style, I sought out some young adults across the parish who I thought would be able to contribute to some of the different components of a seminar — some teachers from a local Catholic school and a tailor who is a Catholic convert with a powerful story. I rode my back across the parish twice to meet with them and discuss the schedule and content of the seminars, and by the eve of our first one, I felt ready to go.

Until everyone I had asked to help backed out the evening before the first seminar — one had a sick relative at home, the teachers had to stay back to administer Saturday exams, and I was left on my own to figure out what to do. I quite literally scrolled through all of my contacts from here in Utegi wondering who might be able to help and remembered another teacher and our own sacristan – I called them that Friday night, gave them the low-down, invited them for tea in the morning to discuss our plans more fully, and off we went. I got a big dose of how planning and ministry works here — it’s less about how magnificent of a plan you can make well in advance, and more about being connected with generous people who can help you in a pinch. Village life might be slow in some ways — but in others, everything comes together last minute, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

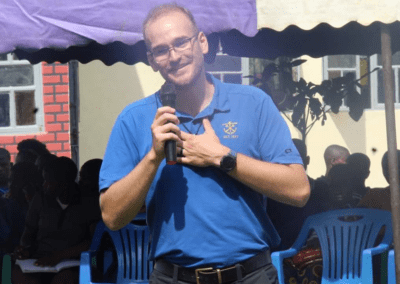

The first seminar was a great success — we had twenty-five young adults from one of the outstations come, some of them not even Catholic but just curious. I gave a talk about human nature, sin, and grace — which may have been a bit of a practice run for my homily the following day. Our teacher gave a talk about kujitegemea, or self-reliance, as a young adult . And we learned and practiced together praying the rosary, which many were not familiar with, and Eucharistic Adoration. We ended with a sense of energy and zeal, these young people excited to come to know their faith more deeply and live it together.

Over the course of the month I learned not to worry endlessly about details and personnel. As long as I made sure there was food when we finished, the Eucharist to share or to adore, and sufficient information inviting the young people to come, we’d be good to go. Gradually, I began to see the genius of these semina too. For poor people like our parishioners, many of the activities I think of as typical for young adults are not feasible: meeting for drinks or food, having a multiple-day retreat, traveling to a place of pilgrimage, or even meeting virtually (most don’t have smartphones). In a way, the lack of funds for travel or technology is also the seed for local bonding and creativity. Really, it’s awesome how well these young adults know each other and how easily they work together.

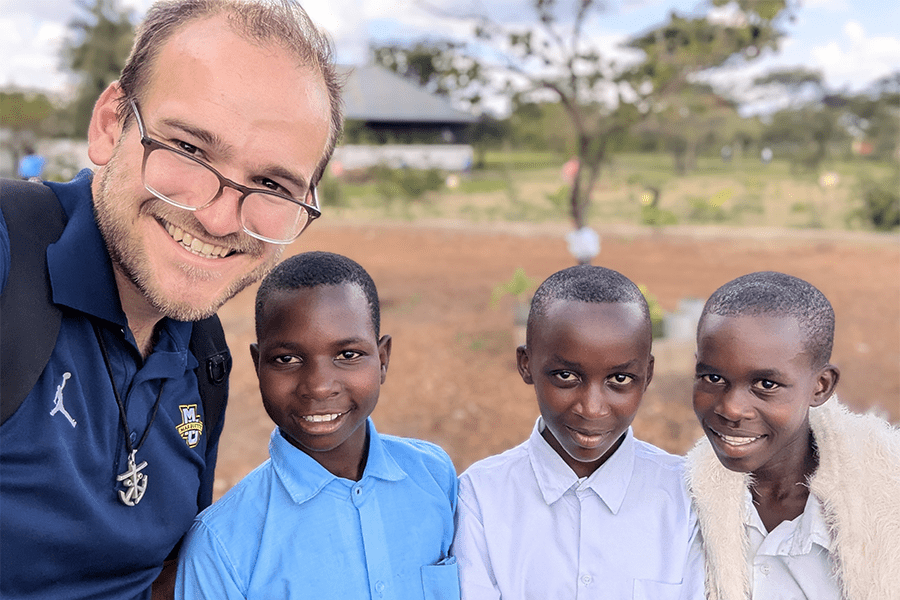

Finally, then, by the end of the month we had the “mega-semina” with young adults not only from this or that village, but from all eight of our churches. In the weeks leading up to the seminar I realized that the major issue would be transportation. It was unreasonable to expect those who live 5+ miles away to walk to our main church in the morning and return in the evening — and even those who could, from 2 or so miles away, would much prefer to catch a lift. The problem, of course, is that the old pickup I drive could, at maximum, fit fifteen people or so in the back, fairly unsafely. That would mean 10 shuttles to pick up the 150 people or so that I expected. So, I went out on a limb and asked one of our parishioners, David, who has a “lorry,” or a large tarp-covered truck, if he could lend us the vehicle in the morning and evening. He graciously agreed and even offered to drive. We set a route plan, announced it at every church the Sunday before the seminar, and at 7:30am before the seminar we set out to fill the bed of his lorry, not with cement or sand or bricks, but with humans! We made a big loop around the parish, from church to church, waiting for stragglers when needed. And by 9:30am we were back at the parish compound with over 100 young people to unload.

We met another 150 who had come walking, many from the local schools. When we passed around an attendance list we realized we had over 260 young adults — over 100 more than we had planned for — and had to find some extra rice, beans, and vegetables to throw in the pot to make sure they were fed. The seminar continued like many others, except that we had guest speakers from Holy Cross Family Ministries — experts in leading these seminars who had traveled from our parish across Tanzania in Arusha. The first talk was on “living a purpose-driven life,” the second was on “life of prayer as a young adult ,” and the third was a question-and-answer session to address the more pressing concerns for young people. Sprinkled throughout were the kinds of fun games and ice-breakers you might expect for youth. We closed with a very lively Mass — the young adults basically filled our whole church on their own and sang with all kinds of energy.

It was a seriously joyful day for me. I felt like my efforts encouraging and wrangling the young adults had basically paid off. Besides becoming familiar with what a semina actually is, I’ve also become familiar with our young adults from every corner of the parish. And now, knowing all these folks, I can get to work for the next eight months helping them become disciples and leaders in their own communities. Really, these people face serious challenges: poverty, lack of education and opportunity for work, and for young women especially, the lack of agency to chart the course of one’s own future. But none of that stops them from having a hunger: a hunger for a life that is abundant, a life that is full, and a life lived with God. I thank God for my vocation which has brought me to this corner of the world to walk with these young adults as they transform these earthly villages, bit by bit, semina by semina, into the heavenly kingdom.

Support Holy Cross in East Africa: Give Today!

Published: November 6, 2024

Dates for Year of Mission Planning

Dates for Year of Mission Planning All Holy Cross apostolates and partners are invited to participate in the Congregation of Holy Cross’s ongoing...

Winners of the 2025 Holy Cross Missions Student Essay Contest

The Holy Cross Mission Center, in partnership with the U.S. Province’s Office of Apostolic Mission & Charism, is pleased to announce the winners...

In Memoriam: Rev. Francis D. Zagorc, C.S.C.

The Holy Cross Mission Center is committed to sharing the stories of Holy Cross missionaries from the U.S. Province who dedicated their lives to...