Letters from Nyumbani, Part VI: “Kujitegemea: Self-Reliance and the Future of the Church” by Keenan Bross, C.S.C.

In the “Letters from Nyumbani” series of reflections, Moreau seminarian Keenan Bross, C.S.C., shares his experiences during his pastoral year at St. Felista Catholic Church, a Holy Cross parish in Utegi, Tanzania. The series title includes the Swahili word “Nyumbani,” meaning “home,” a reminder that for Holy Cross religious, “Often we must make ourselves at home among more than one people or culture” (Constitution 2 of the Congregation of Holy Cross).

———

Kujitegemea: Self-Reliance and the Future of the Church

One of the most oppressing experiences of any Mzungu or white person in East Africa is begging, all the time. Not only from the kind of folks who might typically beg from you: homeless, hungry, etc. But just about anyone who sees you has the idea that a Mzungu has pockets overflowing with cash they’re just waiting to give out. Even in Utegi, where people know I am a seminarian and not a businessman, I am asked daily for money for soda or tea, for my water bottle or my books, even for the bicycle that I’m riding. Closer friends will ask for help with running their businesses or paying for their students’ tuition or chipping in for the costs of a funeral. These endless requests are exhausting, not just because I simply have no way whatsoever to help everyone who asks, but also because the needs are often genuine. People are poor, and when they lay eyes on you, they see a possible way out of that condition.

When I brought this (fairly ordinary) challenge to my mentor, Fr. Robert Luvakubandi, he really helped me flip my perspective around. You do well, he explained, to let people down, not only because you simply don’t have enough. But also, he went on to say, we really need a sea change in our people’s idea of who the Church is and whose job it is to build it up. In other words, he got to explaining to me the real meaning of Kujitegemea.

For the longest time, missionaries from other congregations, especially in our area of Tanzania, came to the villages with big hearts and deep pockets. When a new Church was needed, they built it. When a parishioner needed to go to the hospital, they paid for it. When children needed to go to school, they sent them. In Swahili, we would call this system Kutegemea, or dependence. The Church and even their own communities were something people attended, not something they built. Fr. Robert explained to me that what I’m experiencing, as a Mzungu, is the vestiges of that old system.

What’s at stake every time I’m asked for something, he explained, is whether or not you want to reinforce people’s older idea of what the Church is and who’s responsible for it, or if you want to usher in a new one. In other words, if you want to put the “ji” in kutegemea. In Swahili, when you put “ji” in a word, it makes it reflexive. Kuandaa is preparation, kujiandaa is self-preparation. Kuuliza is to question someone, kujiuliza is to wonder or to ask oneself. So whereas kutegemea means dependence, kujitegemea means self-reliance. For Fr. Robert, teaching and living kujitegemea is the only option for a bright future for the local Church in Tanzania.

Kujitegemea has a long history in Tanzania. It was core to the founding philosophy of Julius Nyerere, the first president of Tanzania, whom the Church has named a servant of God. Birthing a nation at the height of the Cold War, Nyerere had a staunch policy of non-alignment. Tanzania would not become a proxy-communist or proxy-capitalist state. It would not allow outside organizations like the World Bank or the IMF to chart its future. Tanzania would be the agent of its own future and use whatever help it could find along the way as precisely that: help. Africa’s only path out of dependence on its former colonizers was a fierce resolve to depend on itself, to build an economy and community, language and identity of its own.

What I don’t think I realized, at least at first, was the way that kujitegemea has trickled down from being a national philosophy to a local one. One of the biggest cultural shocks for me in the first few months, really, was just how often we talked about money in Church. In the U.S. context, we try to reserve asking for money or talking about finances to just a couple of Sundays per year—maybe for the Bishop’s appeal and Stewardship Sunday. But here, in most of our churches, money-talk is a daily event. In addition to the three main contributions every Christian makes (sadaka, shukurani, zaka—”offertory, thanksgiving, and tithe”), nearly every Mass or Communion Service is followed by an appeal to fundraise for this, that, or the other. We call these michango, or contributions.

Michango can be for many things: building or improving the physical church, attending an event or pilgrimage, bereaving a neighbor’s family, even gathering foodstuffs for the priests. People normally contribute in micro-amounts: a quarter here, $1 there, or maybe $5. But these are serious contributions for most of our people, and they have to dig deep in their pockets to find the money. Which is why, for the first few months, I really felt like “goodness, these michango are like taxing our poor people to death.”

In time, though, I realized that these contributions were not driving people and their pockets away. Rather, they gather people and are a source of unity. When you contribute to something out of your own pocket, when it comes from your own sweat and blood, there comes a real sense of ownership. I was beginning to see what Fr. Robert insisted on: kujitegemea is the future, not just because we’re out of money from benefactors; it’s who we are as a Church.

One of our village churches has been a fascinating example of this, Bukwe. The priests who have been here for some time said that four years ago we were praying in a tiny, hot, stuffy Church where we might have 15 or 20 Christians show up on a given Sunday. Over the past three years, we’ve worked with the Christians to build up their own Church—the Holy Cross Mission Center supporting with some key materials like cement, iron bars, and roofing; the Christians contributing the rest along with all of the labor. Now, the beautiful church is one of our most vibrant in the parish. There are easily 150 and maybe 200 Christians there on any given Sunday. We baptize and marry many of them each year. And many of my most active young adults gather there each week. Truly, as they say, “if you build it, they will come.”

The new frontier for me, now, in learning and promoting kujitegemea is what we typically call miradi, or projects. As I become more familiar with our different groups—young adults, women’s group, Legion of Mary, etc.—I am consistently surprised by one thing. They are so, so serious about starting projects. Starting a garden or a farm, making soaps and shirts, crafting rosaries, and the like. There’s this sense that for us to be together, we should be doing together. And there’s a hope that the income from these projects will allow us to do more together as a group: go on pilgrimage, have seminars and gatherings, and—of course—have matching shirts.

This month, we started our first mradi with those very young adults of Bukwe. I bought about $40 worth of materials for making rosaries (beads, crosses, centerpieces, and cord). We invited a sister from a neighboring convent to teach us. And we had a 5-hour class with around 20 young adults, together with lunch (which people chipped in to cook), and made over 40 rosaries to start. Sister emphasized that making rosaries is a spiritual practice, not to be done with noise and chatting, but seriously prayerful. And those who make rosaries have a special obligation to pray themselves.

Really, I have a lot to learn from kujitegemea. The Church is not a business or a service that we missionaries offer and another people receive; the Church is something we become. And in the process of becoming the Church, we will be filled with the Holy Spirit, and we will renew the face of the earth. I have no issues, now, turning down requests for this or that assistance. Not because my heart has grown cold, but because it has been filled with hope. With a vision of a people who, bound together by their michango and miradi, and most importantly their faith, will form and grow the Body of Christ for generations to come.

Published: February 11, 2025

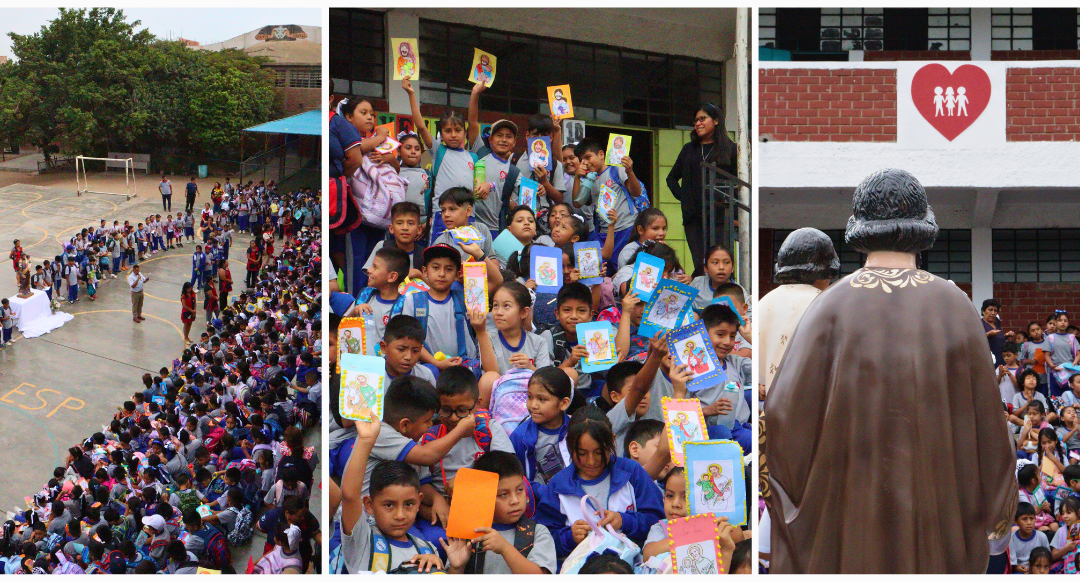

Faith Abroad: The Feast of St. Joseph in Chile & Peru

The Feast of Saint Joseph was celebrated with joy and devotion across the District of Chile-Peru, uniting the Congregation of Holy Cross, including...

April 2025 Prayer Intention of the Superior General

All are invited to pray along with Superior General Br. Paul Bednarczyk, C.S.C., this month: For those who will receive the Sacraments of Initiation...

Celebrate With Us! The Year of Mission Begins on April 28, 2025

The Congregation of Holy Cross invites all friends, collaborators, and ministries to join in celebrating a landmark spiritual initiative: the Year...