Letters from Nyumbani, Part VIII: “Language: Knowing Others, Knowing God” by Keenan Bross, C.S.C.

In the “Letters from Nyumbani” series of reflections, Moreau seminarian Keenan Bross, C.S.C., shares his experiences during his pastoral year at St. Felista Catholic Church, a Holy Cross parish in Utegi, Tanzania. The series title includes the Swahili word “Nyumbani,” meaning “home,” a reminder that for Holy Cross religious, “Often we must make ourselves at home among more than one people or culture” (Constitution 2 of the Congregation of Holy Cross).

———

Language: Knowing Others, Knowing God

Back in September I was visiting one of the bigger cities in Tanzania, Arusha, and met a number of young Swiss entrepreneurs running businesses here in Tanzania. Some of them, they explained, actually grew up in Tanzania – their parents the children of former colonists who remained after independence. When they heard me speaking Swahili with locals, they were shocked: “How is your Swahili better than ours after two months here, when we have lived here most of our lives? What is your secret?” I told them that, unlike them, who live in a big city where people speak English and work in offices all day, I am – as they say here – “deep in the village.” When you have no other option but to speak Swahili all day, and it’s the heart of your mission, you end up learning pretty quickly.

Truly, the journey of learning a new language is one of the greatest blessings and adventures of a missionary. One of our lifelong missionaries was known to insist that “if you love the people, you will learn their language.” Surely, learning a language is a bit like falling in love. Every new word or piece of grammar that you pick up is a dive a little deeper into the language. And yet it is bottomless, there is always, always more to learn. It takes effort and intentionality – flash cards, clarifying discussions, and a dictionary close to my bed. The greatest tool is imitation, doing your best to sound like the people you are with, using their turns of phrase, their filler-words, and their pronunciation. In the end, a bit like falling in love, you wind up resembling the folks that you’re with.

After 7 months living here, I have developed a particular love for Swahili, or Kiswahili, to be more precise. The language itself reflects the history of this region: 70% comes from the Bantu peoples of sub saharan Africa, 20% from the Arabic traders who settled on the Indian Ocean, and another 10% from colonial influences. It has the beauty of Arabic, the precision of German or English, and the vitality of Bantu languages, rooted in creation and community. And though sometimes I am frustrated by its immensely long verbs, like Hatutakusahau (meaning, we won’t forget you), its robust grammatical structure is satisfying once you get the hang of it. Moreover, the language is a powerful force for unity here in Tanzania. Whereas many sub-Saharan countries are sharply divided by ethnic and language groups, Tanzanians from every corner of the nation do business with one another, listen to the same music, and do politics with one language – which is perhaps part of why Tanzania has never had a coup or civil war in over 60 years.

The oldest members of society, raised before independence and the proliferation of Swahili, often are much more comfortable in their tribal language. And while in some areas of Tanzania, parents are no longer teaching their children their “mother tongue,” here in Utegi Dholuo, the Luo language, is still dominant on the streets, in the market, and at the football pitch. Since when I arrived I still had much work to do with my Swahili, I never took up learning *Dholuo* in earnest — at the moment I can string together some very simple sentences – subject + verb + object – as well as do basic greetings. Frustratingly, Luo and Swahili have basically nothing in common, and Luo has all kinds of sounds that I haven’t learned to make in English or Spanish or Swahili or even Bangla.

For the most part, really, I haven’t needed to know Dholuo, but when I’ve been bringing communion to the elderly it always felt a bit off to read Scripture with them in a language they hardly understand (Swahili). Recently, I acquired a Dholuo Bible and began visiting the elderly with it along with someone who can read for me. “Biuru ira, un doto mujony kendo mugangoru mapek, mondo amiu yueyo” – Come to me all you who are weary and heavily burdened, and I will give you rest. Although I catch basically nothing, it’s been amazing to see the way these elderly people come alive hearing the Word of God in their own language. If I’m with a Luo catechist, it’s beautiful to hear them reflect on the Word of God and explain the Eucharist in Luo. I might be lost trying to listen, but the Bibi and Babu, grandmas and grandpas, we are visiting nod their heads, smile, respond, and even laugh as the Word of God comes alive in their own language.

Sitting outside of the home of Prisca, an elderly woman, last week I was nearly brought to tears by the event. She had recently suffered a fall trying to enter her home and busted her wrist, clearly in pain and distraught by the whole situation. As we opened the Bible and the Word of God reached her eyes, I was overwhelmed by wonder at the way the Church has translated the scriptures from Hebrew to Greek into thousands of languages the world over. That, who is truly the Word of God, wanted so much to be with Prisca in that moment that He allows his essence to be carried by the tongues of people from every corner of the earth and every culture. “He humbled himself to share in our humanity,” as the priest says at Mass, even to the point of letting his message be carried totally in the very language that these people learned from the mouths of their mothers and fathers.

Interestingly enough, this very diocese was once a hotbed for the work of translating the scriptures into local languages. Unlike other regions of Tanzania where language groups consist of millions and millions of people, our particular region is known for being highly mixed. Our diocese alone—covering roughly the size of Vermont—has over 40 local languages. Since the proliferation of Swahili throughout Tanzania, almost all liturgy and catechism is done with the national language. But beforehand, the missionaries here had no option but to learn people’s languages. In order to do so, they established the “Makoko language center” which served the dual-purpose of training new missionaries and catechists as well as producing literature and music in the local tongues. I am told very frequently that my “forerunners,” the American missionaries who served in this area until 10 or 15 years ago, spoke absolutely superb Luo. When the locals would go to hear them preach, the faithful would learn new words, not the missionaries.

This mish-mash of languages – where an educated person needs to know an “indigenous language” like Dholuo, a national language like Swahili, and a Western language like English – is actually quite normal in much of the developing world. It’s easy to say that the world would be a much simpler place if we could all just settle on a few languages and leave the other ones to go extinct. But the expansiveness of human language, our capacity to express ourselves in a myriad of different sounds and systems, is arguably much more worthwhile than the efficiency of simply understanding one another. Imagine the incalculable worth of the stories and proverbs cached away in the thousands of languages around the world. All the vocabulary that’s all but inexpressible from one language to the next. Sometimes I even find myself thinking through something in Swahili, satisfied with some particular way of expressing an idea, and frustrated that it doesn’t come out the right way in English! And I am just now learning the language.

Last week, that very same day I found myself in wonder at the Doluo Bible, God wanted to surprise me even more. Just down the road from Prisca’s place, we visited another sickly grandmother and prayed with her. As we wrapped up, she sent someone to call her grandchild, Juliana, who had given birth just last month and wanted to be prayed with, too. When Juliana entered I recognized her and remembered the first time we met – when she was pregnant — and it took me a moment to understand that she was deaf. I was very happy to see her — really, she is one of the most joyful people I’ve met in Utegi. But I had no clue how do go about praying over her when she wouldn’t be hearing what I am saying.

I called up my friend Akinyi, a university student from Utegi who is studying special education and knows Swahili sign language. Turns out, she and Juliana were childhood friends, and that Juliana was part of how Akinyi decided to study special education. She told me to put her onto a video call and hold it where Juliana could speak with her hands easily. I was amazed! Juliana was overjoyed to see her old friend, and the two of them chatted it up. Akinyi began translating for me a bit, telling Juliana how we we’re praying for her and her baby girl and discussing when we could have her baptized. Akinyi explained to me that I could just do the prayer for a mother after birth as normal from our book. Juliana can read Swahili well, so I just needed to trace along where I was with my finger.

At the end of the day, the prayer went smoothly enough. I was most moved, though, by the way we were all gathered together in their simple home with a mix of spoken and signed languages. You cannot tell me that the Latin refrain, Ubi Caritas et verat, Deus ibi est – where true love is found, there is God – did not abound between me and the catechist, Akinyi and Juliana. For all its complications and messiness, language – our ability to know one another and ultimately know God – might be the greatest gift God bestowed on humanity. I thank God for this chance to learn just a bit of one more language and, in doing so, fall in love all the more with Him and His people.

Published: April 1, 2025

St. Joseph’s Hill Students Receive New Computers

When the students at St. Joseph’s Hill Secondary School in Kyarusozi, Uganda were suddenly at risk of not being able to take a newly-mandated...

Moreau Seminary, Dhaka, Completes Renovation

Moreau Seminary in Zindabahar, Dhaka, is currently home to 74 Bangladeshi seminarians who are going through its 3-year formation program. The...

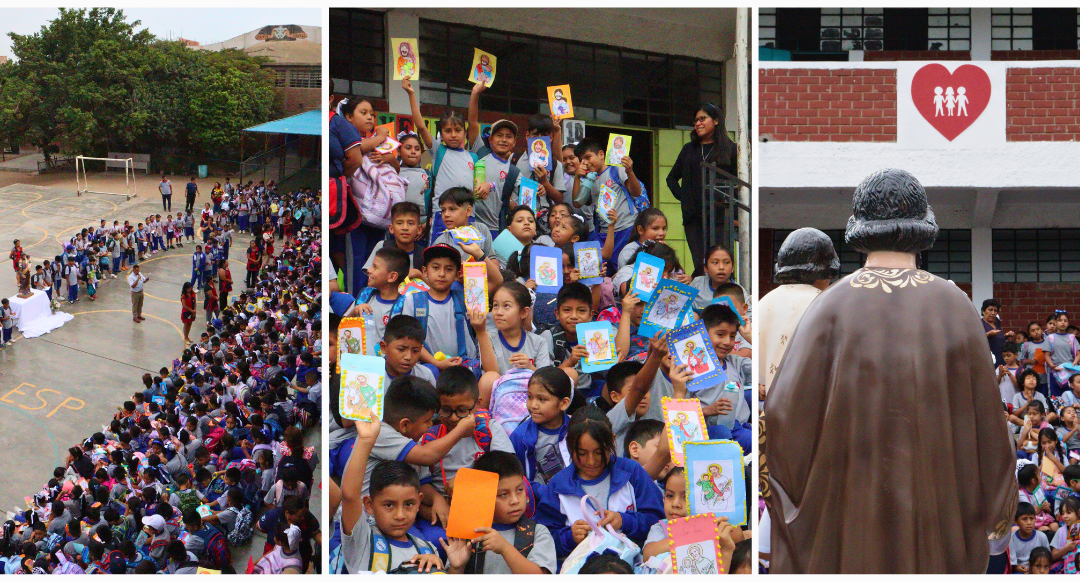

Faith Abroad: The Feast of St. Joseph in Chile & Peru

The Feast of Saint Joseph was celebrated with joy and devotion across the District of Chile-Peru, uniting the Congregation of Holy Cross, including...